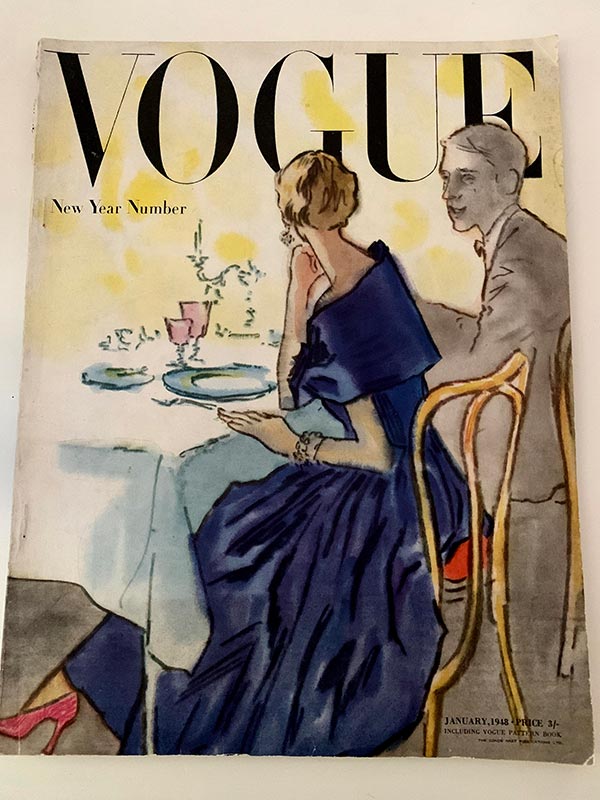

New Year Number January 1948

I have a collection of vintage Vogue magazines, carefully packed away in plastic freezer bags for protection. Not very glamorous, but it’s worked! When I opened them up during lockdown, they revealed a world of glamour. Articles that have defined the way we think about fashion. The first magazine I came across was Vogue 1948, New Year, the year after Christian Dior’s revealed his pivotal “New Look” collection.

This article grabbed my attention;

“We are lucky to live in the first period in history that has found the key to Freedom in Fashion.”

A quote from the article intrigued me;

“The favourite cliché about fashion is that it is a dictator, that’s nonsense, anyway, in the sense that fashion is imposed by an outside force. Fashion is nothing more nor less than the way we like to look, and it’s only when enough of us want to look a different way that fashion is said to “change” …

I believe every time a new trend starts, it’s due to this collective longing for change. I firmly believe the difference in fashion over the ’30s and ’40s was one of the most dramatic. During my research, I found that it wasn’t a societal dictate, but the impact of the second world war that imposed such severe restrictions in fashion.

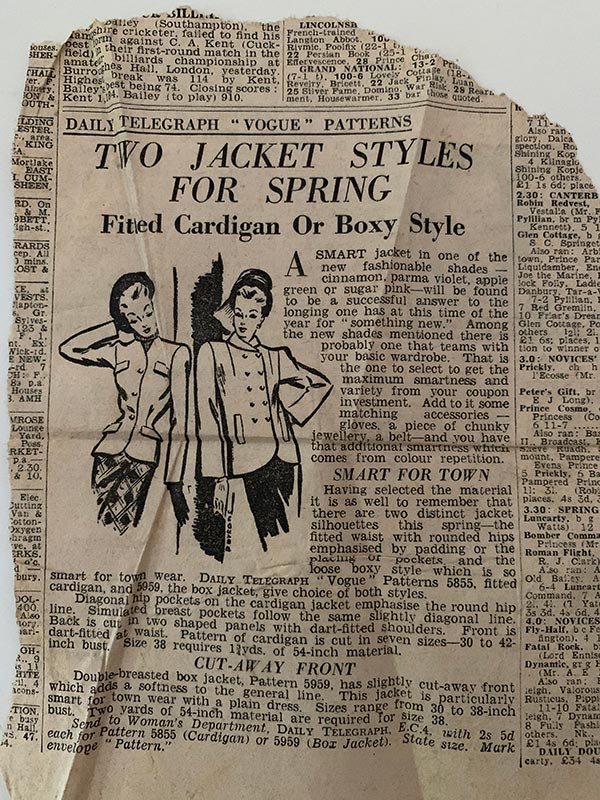

Designs were pared down, to save fabric, clothes were pared down. Clothes incorporated few if any pleats and minimum trimmings. Skirts finished a little below the knee and were worn with fitted or straight, boxy jackets. The overall looks tended towards the severe.

As an example of this, below is a newspaper cutting discovered, folded up in a Vogue magazine, advertising a Vogue pattern. From the drawing, you can see the restricted cut and straight lines which typified the era.

Clothes rationing was introduced in Britain on 1st June 1941, limiting the number of new garments people could buy. This restriction was to last until 1948, and in some areas even beyond. Newly frugal shoppers spent their precious clothing coupons on items they hoped would be suitable across the seasons. Despite the restrictions, war and civilian austerity did not put an end to creative design, commercial opportunism or fashionable trends on the British home front. Clothes were often customised at home and “Make Do And Mend” became the common mantra.

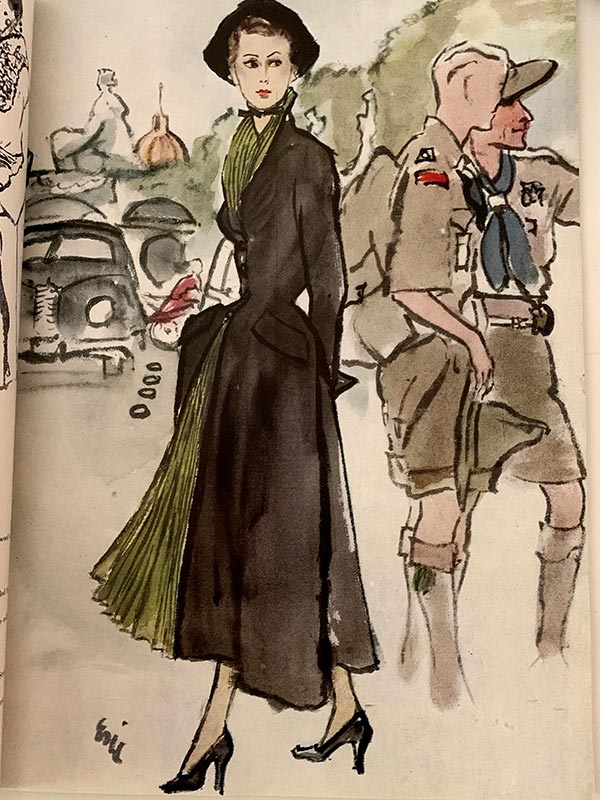

Christian Dior’s “New Look” collection, shown in 1947, ushered in a new silhouette, fitted jackets, bold shoulders, nipped-in waists and full skirts in mid-calf length, it was a crucial moment in fashion. This style put Paris on the map as the world’s fashion capital.

The clipping above, from a newspaper dated March 1948, highlights the influence of Dior’s extravagant use of fabric. As you can see, this is the newest look for spring 1948. The renewed freedom of choice, offering endless options and limitless flamboyance must have been a fantastic feeling.

Although this overtly exaggerated styling enamoured not everyone, the exaggerated silhouette necessitated corsetry, hip-padding, shoulder pads and fuss. Unsurprisingly, the Feminist movement was appalled at the re-introduction of corsetry and long skirts. The Little- Below -The – Knee Club staged a protest in Chicago, raging against Dior’s “New Look” proclaiming,

“We abhor dresses to the floor! Women, join the fight for freedom in the manner of dress!”

Feminists in general viewed these introductions as regressive and a blow to women’s newly found independence as derogatory acts against the repression they fought so vehemently to achieve. Not surprisingly, Dior’s competitors in the industry, who had embraced austerity, and whose reputation rested on producing sleek, pared-back silhouettes were quick to join the ranks of dissenters. Even the legendary Coco Chanel was moved to state publicly that,

“Dior doesn’t dress women, he upholsters them!

To some, Dior’s aggrandised designs were symbolic of the great divide between the classes within society. His lavish and unapologetic creations appealed to those desiring to broadcast their social standing and lack of the imposed frugality of the lower classes.

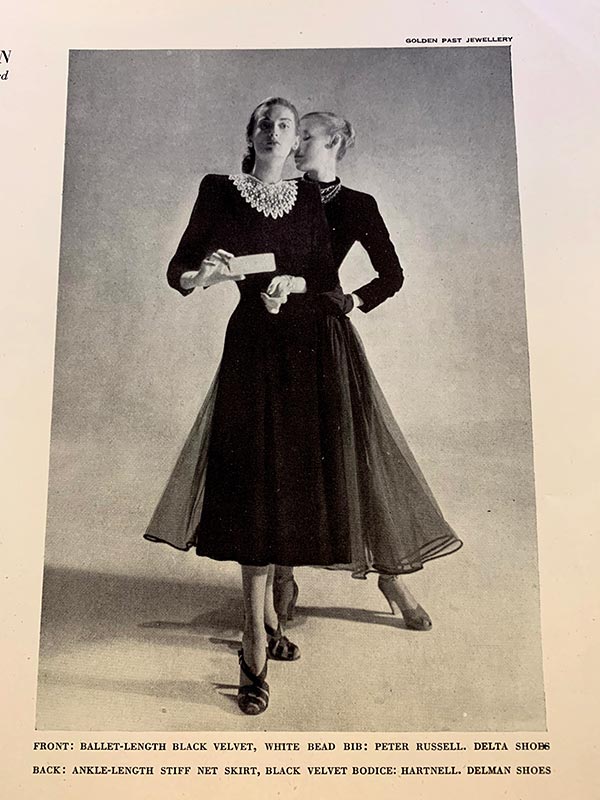

This was an era of opulence, a backlash against the years of austerity imposed by the war. This new abundance filtered through fashion in every respect. Evening dresses could now be floor length and fabulous, ankle, or even ballet length, and endlessly embroidered and beaded. Daywear too became less austere. Jackets were increasingly fashioned from luxurious fabrics, skirts full and frivolous, ‘feminine’ tops embellished with awe-inspiring detail, as the war years restrictions were lifted. Dior was quoted as saying;

” What was heralded as a new style was merely the genuine, natural expression of the kind of fashion I wanted to see. It just so happened that my personal inclinations coincided with the general mood for the times and thus became the fashion watchword. It was as if Europe had tired of dropping bombs and now wanted to let off a few fireworks,”

A rediscovery of prosperity, certainly in terms of fashion, was rekindled during this time. Women across all social classes and generations were able if they wished, or, more tellingly, could afford to, adopt the “New Look”.

The high street, quick to spot a money making opportunity, produced garments inspired by the top fashion houses, but at a fraction of the cost. Those unable to afford couture turned to these high street stores. The more enterprising made their garments, using bought patterns such as the famous “Vogue” brand, producing their versions at a fraction of the cost. By copying the popular fashions of the day and making them affordable, these stores retained the overall style, while making the latest trends available to a broader audience. High street stores catering for the pockets of the working class blossomed, many still surviving to this day.